This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I'm Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

Imagine you're a diplomat, or analyst, or an intelligence officer stationed in a country that's hostile to the United States. You're in your room at the embassy, or hotel, or safe house, trying to get some rest when, suddenly, you feel a pressure in your head, perhaps accompanied by a high-pitched ringing. You feel dizzy, disoriented. The strange part? A clear sense of directionality — the sound and pain seem to be coming from somewhere. Weirder still, as you stand up and move about the room, the sensation changes; certain places in your physical space make it worse, certain ones make it better. Are you under attack?

The cluster of symptoms I'm discussing has an official name: "anomalous health incidents (AHIs)," which is about as descriptive as "unidentified flying object," but you probably know this condition by its original moniker, Havana syndrome.

It was 2016 when the first cases were reported by US personnel stationed in Cuba, though over the years US government employees stationed in China, Europe, and even Washington, DC, have reported similar symptoms. The case count rose into the hundreds, and then above 1000.

The news media were quick to suggest that there was a foreign enemy involved. If you look at the headlines at the time, it appeared almost as a given that this syndrome was due to some kind of weapon:

BBC: 'Havana Syndrome' Likely Caused by Directed Microwaves – US Report

National Defense: Doctors Reveal Details of Neuro-weapon Attacks in Havana

But as the cases increased, the case for the mysterious ray gun hypothesis diminished. Would countries all around the world be sharing this technology? Beyond that, what was the purpose of a weapon like this? It didn't kill its target; it didn't even really incapacitate them (although some affected individuals had symptoms persist into the long term). Was it just supposed to mess with us? The idea of secret weapons became relegated to the tinfoil-hat crowd.

There are, of course, other explanations for the syndrome besides ray guns of unknown provenance. The affected individuals are under a tremendous amount of stress, doing jobs that many of them can't even give us details about in territory which is potentially hostile. Could these events be manifestations of that stress? Some have suggested that Havana syndrome itself is a form of mass hysteria, a boogeyman syndrome propagated not by pulsed energy weapons but by word-of-mouth and word-of-media from diplomat to diplomat, from intelligence officer to intelligence officer. The very stories of the syndrome heighten the stress in those environments, putting these people under more pressure, making them more susceptible to the syndrome.

The distinction between psychosomatic disorder and attack on our own personnel could not be more important. One calls for support and treatment; the other, potentially, for counterattack. Figuring this out is not only of scientific interest but of national interest.

And figuring this out has proceeded across multiple fronts, including animal studies. The pentagon has reportedly been testing directed energy weapons on ferrets to see if they can recreate the syndrome.

But for today, we are going to examine the latest report of the National Institute of Health's AHI Intramural Research Team, who measured, well, almost everything you can think of among patients with Havana syndrome. Their results appear across two papers appearing this week in JAMA.

I'm going to start with this study, which describes the bulk of testing.

Eighty-six patients with Havana syndrome, referred through federal agencies, were included. About half of these 86 had what you might call the classic findings of Havana syndrome:

Acute onset of head-auditory symptoms

Nearly simultaneous vertigo or pain

Strong sense of directionality

Absence of alternative medical conditions

The rest had less typical presentations. The study also included 30 "vocationally matched" controls who were asymptomatic.

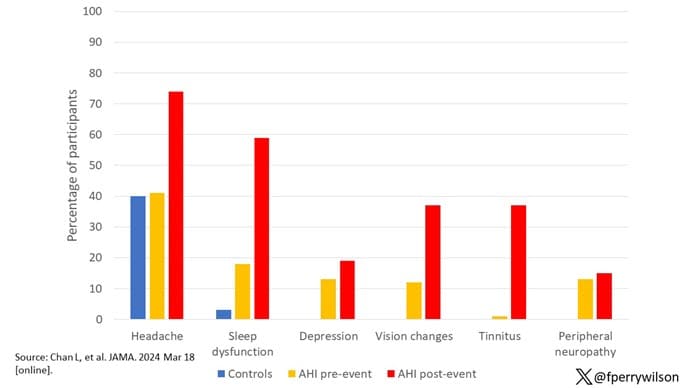

The cases were pretty severely affected: 33% had a reduced capacity to work because of ongoing symptoms. It's worth noting that the cases and controls were not perfectly matched at baseline. Prior to the AHI, those who would go on to develop Havana syndrome had higher rates of depression, tinnitus, and peripheral neuropathy. Of course, as you can see, the rates of these conditions went up dramatically after the AHI.

Looking at those changes from before and after the AHI, you notice one common thread: Most of the changes are in subjective areas, stuff that is hard to measure with blood or imaging tests. After an AHI, the patients report more depression, headaches, sleep dysfunction, cognitive complaints, dizziness, and loss of balance. Would these complaints translate into biomarkers that could be measured? A ton were measured in this paper, but, basically, the answer is no.

Formal neurocognitive testing showed that those with Havana syndrome were no different from controls in terms of intelligence, memory, processing speed, or reasoning.

Blood levels of glial fibrillary acid protein and neurofilament light chain levels (markers of brain injury) were also the same across the groups.

The second JAMA paper used advanced MRI techniques to look at total brain volume, white matter, gray matter, connectivity domains, and so on and found essentially no daylight between the cases and controls — the only exception being a slightly larger corpus callosum volume in the cases, which is actually the opposite of what you would expect after a brain-damaging insult.

Looking at this heat map of all the factors measured, you only see one area where there are significant differences: the psychological assessments.

Those with Havana syndrome had markedly worse scores on the Beck Depression Inventory, worse scores on the PTSD scale, and much lower life satisfaction.

In other words, these individuals are suffering. But it's unclear from the testing why they are suffering. The weight of evidence is stacking up firmly against the idea of some mysterious weapon. The CIA has actually created a report that states it is very unlikely the syndrome is the result of an adversarial attack. Given the state of trust in our government these days, that conclusion may or may not make you feel better about the whole thing. Congress doesn't like it. Last month they said they would investigate the CIA assessments themselves.

Look, there are a lot of "ifs" here. If these studies are accurate, and if the individuals in these studies are actually representative of those with Havana syndrome, and if the information available to certain agencies but not to us is generally in line with these findings, it seems likely that the syndrome is a manifestation of depression and PTSD as filtered through the perception of those embedded in a hostile environment. If not, well, perhaps wearing a tinfoil hat is not the worst idea in the world.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale's Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and his book, How Medicine Works and When It Doesn't, is available now.

Credits:

Image 1: F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE

Image 2: JAMA

Image 3: JAMA

Image 4: JAMA

Medscape © 2024 WebMD, LLC

Any views expressed above are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of WebMD or Medscape.

Cite this: The Most Extensive Study Yet of 'Havana Syndrome' Turns Up… Nada? - Medscape - Mar 19, 2024.

Comments