This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I'm Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

For most of human history, the spectacle of a solar eclipse was terrifying. Cultures around the world have strikingly similar mythologies around this celestial event. Chinese writings describe a dragon eating the sun.

Norse mythology suggests the sun being consumed by a great sky wolf, and the Incas thought their sun god had been attacked by a jaguar.

In all these cases, an eclipse was a bad omen, a sign that the ruler would soon die, or a war would break out, or famine would come. Sometime in the 5th century BC, the first human documented to predict an eclipse was the Greek astronomer Thales of Miletus, according to Herodotus.

A century later, Anaxagoras theorized that a solar eclipse was caused by the moon's shadow, though his geocentric view of the event was off. We would need Copernicus and Kepler before the real orbits were understood.

And so, just as our understanding of the science of lightning changed our experience of a thunderstorm from one of terror to one of awe, our experience of an eclipse has also changed. We do not fear what will happen on April 8 of this year when a total eclipse of the sun will pass over much of the country, but according to a new study, perhaps we should.

Two hundred million Americans live within driving distance of the path of the total solar eclipse that will cross over the bulk of our country in early April. And I, like many of those 200 million, will be getting on the road to position myself somewhere along that path of totality. Side note: I thought I was being clever by calling a ranch in Texas to reserve a spot about a year ago; they told me they had been booked solid for at least 3 years. Damn you, Kepler.

We are talking about eclipses on Impact Factor — nominally a venue for medical commentary — not only because they are incredibly cool and it's nice to take a break from the usual randomized trials and tribulations, but also because of a study appearing as a research letter in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Researchers Donald Redelmeier and John Staples were worried about the risk for traffic accidents during the upcoming eclipse. How can we understand the risks? We can turn to history. And we don't need Herodotus for this one.

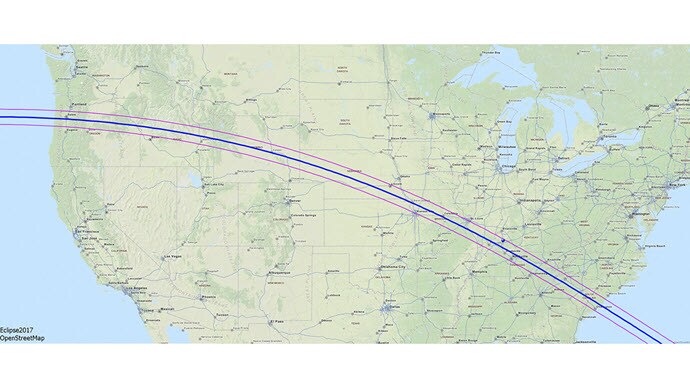

On August 21, 2017, the shadow of the moon traced this path across the United States, coming within 3 hours' driving distance of one third of the population.

Using data from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration Fatality Analysis Reporting System, researchers evaluated whether fatal traffic accidents increased during the eclipse period. To be fair, the maximum duration of this particular eclipse was 2 minutes and 42 seconds in Carbondale, Illinois. It would be really hard to study the risk for traffic fatalities in a window like this.

No, the authors hypothesized that it might not be the eclipse itself but the stuff surrounding the eclipse that leads to more traffic accidents — more people driving being the number-one factor. But more than that, it could be driving while rushing to get somewhere for an event that cannot be delayed, or the inevitable celebrations that go along with the festival-like atmosphere that a modern eclipse engenders.

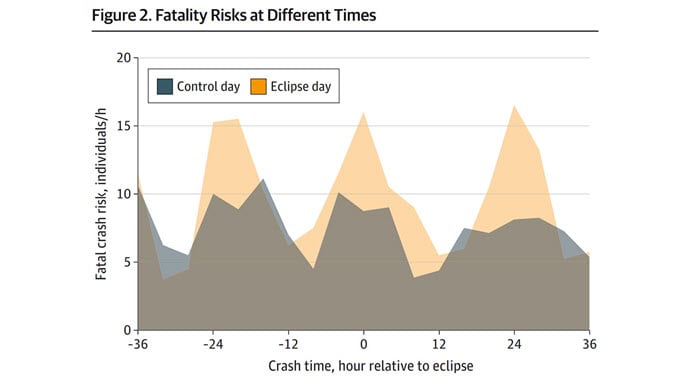

So, they used a 3-day period, centered on the eclipse as their exposure window. For controls, they looked at the same 3-day period a week before and a week after the eclipse.

The primary findings are shown below. As you can see, during the days surrounding the eclipse, there was a significant increase in traffic fatalities — on the order of around 30% higher than the control periods. This is similar, in fact, to the increase in traffic fatalities we see around Thanksgiving, Memorial Day, and the Fourth of July, all big "driving" holidays.

Examining key subgroups, they found that this eclipse effect was stronger when alcohol was involved and when younger people were driving.

What do we do about this, with an imminent eclipse? We can remind people that traffic is going to be a bit worse around the 8th and to give themselves plenty of time to carefully, calmly, get to the place they want to watch the cosmic ballet unfurl.

And, of course, if you are going to look at the eclipse, look at it through something like this — a solar filter. There aren't too many ways the eclipse can hurt you directly, but eclipse-related solar retinopathy is one.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale's Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and his book, How Medicine Works and When It Doesn't, is available now.

Credits:

Image 1: NASA

Image 2: Wikipedia

Image 3: JAMA Internal Medicine

Medscape © 2024 WebMD, LLC

Any views expressed above are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of WebMD or Medscape.

Cite this: A Solar Eclipse Is a Bad Omen...For Drivers - Medscape - Mar 25, 2024.

Comments