Offering colorectal cancer (CRC) screening to patients when they come to the clinic for wellness visits may be the standard of care, but relying on that strategy alone will miss many patients who do not access healthcare regularly.

Although CRC is the second-leading cause of cancer deaths in the United States, rates of screening have not met public health goals. The American Cancer Society and other groups in 2012 called for reaching 80% coverage in every community by 2018, but that threshold remains unmet. Only 72% of adults between ages 50 and 75 years were up-to-date on CRC screening by 2021.

One reason is the rigors of colonoscopy, which is invasive and requires both an unpleasant bowel prep before the procedure and a day off work to recover. Stool-based testing may be a more viable option for many patients, but the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and other groups have found that raising rates of screening also requires a shift to actively identifying and reaching out to patients who are not up-to-date.

Systematic Approach

Patients do appear to respond well to choice. In a recent study, a team at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia offered patients who were behind on their screening the option of colonoscopy or stool-based screening using a fecal immunochemical test (FIT) at the time of initial contact via the mail.

Informational materials describing colonoscopy and FIT were included, and patients received text messages directing them to additional resources for more information.

Nearly twice as many patients completed the stool-based test than those offered endoscopy alone. Six months after the initial mailing, 5.6% of the patients in the colonoscopy-only arm had obtained screening compared with 11.3% in the group offered FIT only and 12.8% of patients given a choice of modalities.

Shivan Mehta, MD, MBA, associate chief innovation officer at Penn Medicine, had been worried offering patients a choice would overwhelm patients. "As a physician, if I talk to a patient, I can explain to them the pros and cons of different testing," Mehta said. "But it may not be that easy to talk about those two different approaches when you're mailing letters to people."

For Mehta, the key to success was simplicity: "Making it really easy for patients to participate, whether it's through sending them reminders, or mailing people fit kits, or making the scheduling process for completing colonoscopy easier."

In a previous trial, he sent letters to patients who were not up-to-date with screening. Patients who received a letter recommending they call their provider to schedule a colonoscopy were less likely to obtain screening than those who were initially mailed a FIT kit or who received the kit in the mail a month after not responding to the initial letter.

When following up with patients who did not respond to letters in the mail, Mehta learnt method of communication is also critical.

"Texting has been very effective for us," Mehta said. "Even in community health center settings — where they may not have insurance — most of them have a cell phone with texting capabilities."

And texting can be automated, requiring fewer resources than having clinic staff make follow-up phone calls.

Ma Somsouk, MD, said another way to boost rates is to focus on patients who are newly eligible for the screening. Somsouk, a professor of medicine in the Division of Gastroenterology at the University of California, San Francisco, has found success with mailed FIT outreach among patients between ages 50 and 51 years. In a recent study, he found these newly eligible patients were more likely to complete testing (58%) than patients aged 52 years and above who were behind on testing (41%).

The older group was "more refractory to screening," said Somsouk, who concluded newly eligible patients may benefit more from targeted outreach.

"We know that in the absence of any organized approach to screening, we allow people to fall through the cracks," Somsouk said.

His goal is to promote organized screening programs by leveraging digital data collected in most electronic medical record systems.

"We have various ways in which we can indicate individuals who are eligible and not up-to-date for cancer screening. We can look back and find when they're last FIT or their last colonoscopy was, and then we can provide services that can be scaled and automated for individuals," he said.

Another critical aspect of reducing rates of CRC is the coordination of care between primary care and gastroenterology to ensure appropriate follow-up for patients with positive FIT results. Somsouk said clinics should prioritize tracking and monitoring efforts for these patients.

"We as a health system should recognize that they need to get the colonoscopy; otherwise, they're at risk for late-stage cancer," Somsouk said.

All Screening Is Local and National

The CDC has relied on population-based approaches to CRC screening since 2009, when Congress began funding the agency's Colorectal Cancer Control Program. Previously, the agency had focused on a pilot screening program providing test kits to low-income adults whose insurance did not cover CRC screenings. Thomas Frieden, MD, MPH, the then director of the agency, pushed the program in a new direction with the additional funds.

"He encouraged us to do evidence-based interventions in clinics, more of a systems-change model, which is what we do now," said Lisa Richardson, MD, MPH, director of the Division of Cancer Prevention and Control at the CDC.

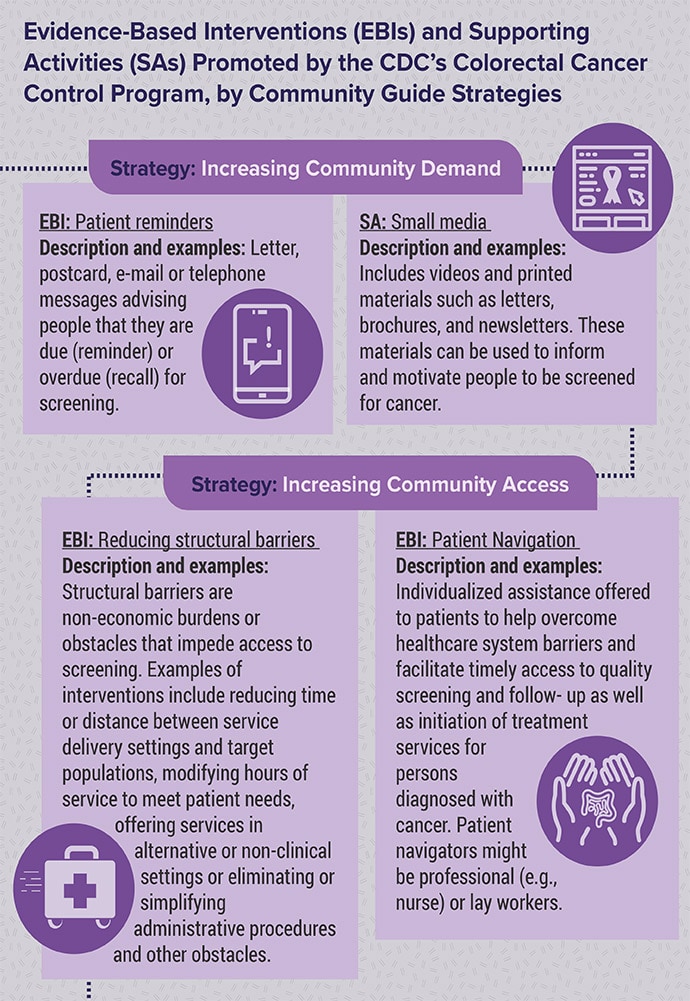

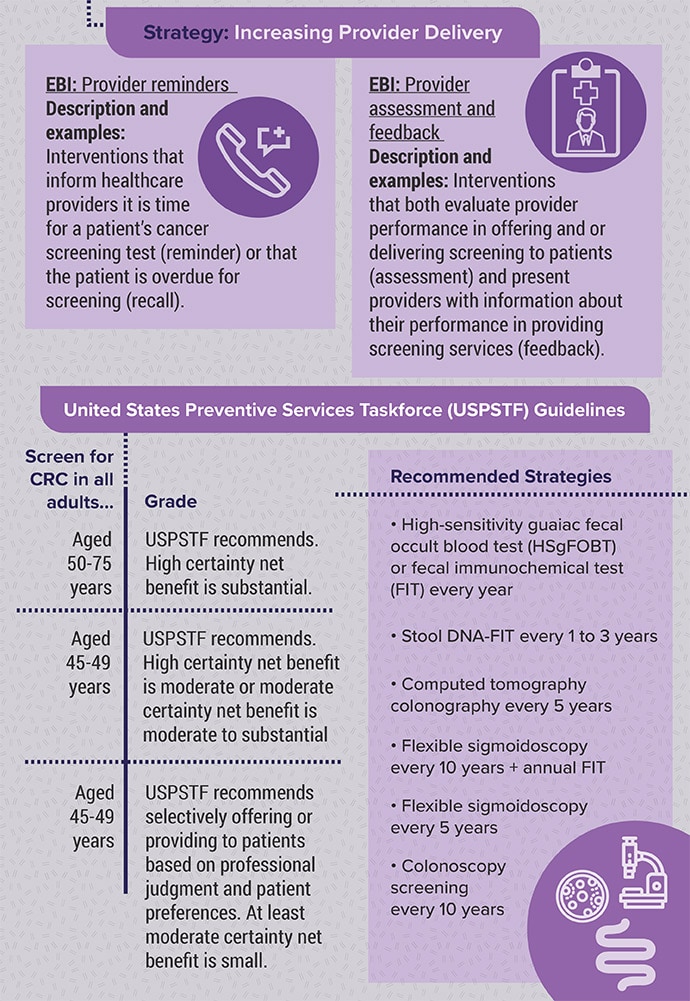

The agency currently funds 35 partners like state health departments and tribal organizations to work with clinics serving high-need populations. They typically rely on a menu of evidence-based interventions (EBIs), such as extending clinic hours, opening additional locations, and offering patient navigators to provide individualized assistance to help patients access screening and follow-up treatment if needed.

Clinics also are encouraged to embed reminders in electronic health records indicating a patient is due for screening or feedback to providers on their performance. According to Richardson, the responsibility of increasing screenings should not fall on the shoulders of individual clinicians.

"It really is about changing the way the clinic does business," she said.

A review of data from the Colorectal Cancer Control Program showed implementing a single EBI did not increase rates of screening. The greatest increase, 7.2% in 1 year, occurred in settings that use at least one intervention from each of these three strategies: Client reminders, provider assessment and feedback, and reducing structural barriers such as simplifying administrative procedures or prior authorization requirements.

"The more of those you implement, the more increase you get in your screening prevalence," Richardson said.

Choose Your Method

The US Preventive Services Taskforce does not state a preference for either a stool test or colonoscopy.

Research showed FIT testing is more appealing to patients. Although colonoscopies have long been the gold standard screening, new cancers or polyps have occasionally been found in patients undergoing repeat colonoscopy, studies have found.

The FIT detects antibodies to hemoglobin and has a better sensitivity of approximately 75% than the older guaiac fecal occult blood test (gFOBT). The FIT is also easier for patients to perform at home because the gFOBT test requires submission of three stools and abstinence from certain foods and medication.

Newer stool-based DNA tests detect genetic shed from neoplasms into stool. Research has shown these tests have a sensitivity of over 90%, but the false-positive rate for the stool DNA test (13%) is higher than for FIT (5%).

Studies have shown that although a one-time FIT is less sensitive than colonoscopy, the higher participation rates lead to similar rates of cancer detection and decreases in mortality.

"In the head-to-head studies that look at FIT versus colonoscopy, generally what we see is that just not as many people follow through with colonoscopy," Somsouk said.

Somsouk said that he tries to avoid advocating one test over another when seeing patients.

"It's more important to complete the test than to choose or find the exact test," he said, "Any test is better than no test."

Mehta reported receiving funding from Guardant Health and the American Gastroenterological Association. Somsouk reported receiving funding from Guardant Health and Freenome. Richardson reported no relevant disclosures.

A former pediatrician and disease detective, Ann Thomas is a freelance science writer living in Portland, Oregon.