This discussion was recorded on March 8, 2024. This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Robert D. Glatter, MD: Hi. Welcome. I'm Dr Robert Glatter, medical advisor for Medscape Emergency Medicine. Joining me today to discuss an entity known as post–intensive care syndrome (PICS) is Dr Nida Qadir, associate professor of medicine and associate director of the medical ICU at Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center. She's also the co-director of UCLA's Post-ICU Recovery Clinic. Welcome, Dr Qadir.

Nida Qadir, MD: Thanks so much for having me. I'm excited to talk about this topic.

Glatter: This topic really caught my eye because of the title of an article you co-authored, " Survival ≠ Recovery." All of us know that surviving an ICU admission can be difficult, that it's age dependent, and premorbid functioning is certainly important. You really put everything in context in a way that was so comprehensive. Therefore, interviewing you about this is so critical in terms of awareness and recognition of the syndrome for all of our providers out there, just so that they have an understanding in order to spot early signs of this.

Can you define PICS, and what are the criteria?

What Is PICS? How Common Is It?

Qadir: Yes, absolutely. I did want to give a shout-out to the lead author of this article, Dr Emily Schwitzer, who was one of our graduating fellows. The article is authored by our entire post-ICU clinic team. PICS is essentially a collection of new or worsening health issues that develop after critical illness. These issues can be physical, psychological, or cognitive in nature, and they affect the vast majority of ICU survivors, although with varying degrees of severity.

Glatter: What caught my eye was that, at the time of hospital discharge, as you wrote in your article, and I'll quote this, "Up to 80% of patients who survive the ICU will have PICS symptoms, and although PICS can improve with time, more than half of patients will continue to experience symptoms at 1 year." That's a daunting statistic just in and of itself.

Qadir: It's incredibly common, and I think all clinicians really need to be aware of this, especially in the aftermath of COVID. At the worst of the COVID pandemic, we saw an unprecedented number of people — and young people in particular (people in their thirties, forties, and fifties) — who experienced critical illness, and pretty severe critical illness at that. I do think awareness is rising among clinicians, but still there's a lot of work to do in terms of education.

Glatter: If we look at the number of PICS clinics pre-pandemic and post-pandemic, what are the numbers? Also, in terms of where we're seeing the greatest number of these clinics, is it academic centers? Are there some in rural settings? What is your understanding of this?

Qadir: In terms of the number of PICS clinics in the United States, we don't have the greatest statistics. Before COVID, it was estimated that there were probably around 20 or fewer in the US, although these were more common in Europe. After the pandemic, fortunately, one silver lining has been that there's been a growing awareness of PICS and many more PICS clinics have popped up, but they do tend to be located at academic centers, which presents another challenge. Not all patients live near academic centers, and patients who live in more rural areas are going to have challenges with follow-up just based on geography.

Clinical Manifestations of PICS

Glatter: How do we manage it when we recognize it? Modifiable and nonmodifiable risk factors certainly exist. Could you discuss some of these factors that we could look to in terms of trying to address it if we see development of it?

Qadir: Sure. It might be helpful to talk about the findings because they can be quite variable. Again, there's variable awareness about all of them.

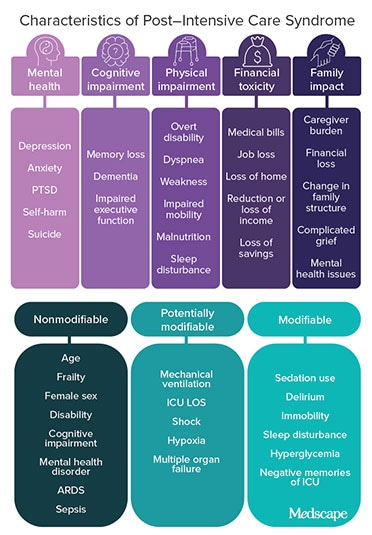

PICS essentially spans the spectrum of all the bad things that can happen. We typically separate the types of impairments that can occur into physical function, mental health, and cognition.

In terms of physical function, some of the findings that I think are becoming better recognized include issues like ICU-acquired weakness and impaired pulmonary function. Other things like malnutrition, wounds from the ICU stay, or developing or being diagnosed with a new chronic condition like chronic kidney disease or diabetes are also part of the physical manifestations.

In terms of the psychological findings, people can develop depression, anxiety, or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after their ICU stay, and some of these things can extend to their family members, unfortunately.

Regarding cognitive deficits, I think this is the area where there's probably the least amount of awareness. These could include things like memory loss or a decline in mental processing speed or executive function.

While these issues can occur in isolation, many patients will experience symptoms in multiple domains, with many things happening together. In terms of managing and preventing these issues, the first big step is diagnosis, which can present with challenges and is a primary reason why we need PICS clinics.

Managing PICS Symptoms

Glatter: I think the recognition and the awareness are so vital in terms of management. Some of the things that come to mind include mechanical ventilation in and of itself being a significant risk factor in terms of developing PICS, as well as other issues with delirium. The duration of delirium in your article was one of the key factors in terms of outcome.

Managing delirium is something that we're always looking to in terms of side effects of medicines, looking at sleep, use of steroids, and neuromuscular blockers. Also, having family members, psychological support, knowing day vs night, and an awareness of all these things is so vital to helping patients overcome some of their symptoms, but also in prevention.

Qadir: Yes, absolutely. In regard to prevention, you hit on a couple of big risk factors for PICS, which are delirium and mechanical ventilation. While precise methods for prevention are very much an area of ongoing research, the things we need to focus on are delirium and immobility, and immobility often comes with mechanical ventilation. In regard to delirium, as you mentioned, longer duration of delirium is associated with a decrease in long-term cognition. Is this patient so delirious because they're so severely ill?

Some of that may well be preventable. Some methods we have for delirium prevention and management, some of which you alluded to, include minimizing sleep disruption, frequent reorientation, and minimizing unnecessary sedation. This is a big one that sounds simple, but it can be hard to implement. Also important in patients who are on sedation is performing daily awakening trials.

In terms of mobilizing patients, that's one of those things that sounds really simple but it's really hard to do. That may reduce the risk for both ICU-acquired weakness as well as cognitive dysfunction. Keeping an intubated patient sedated and immobile is much easier than waking them up and walking them around. You need people to support them physically, move the ventilator, move the IV pole. It's a whole crew.

Glatter: Muscular activity stimulation seems to be so vital in terms of making patients improve at a much more rapid clip. What do you see as the percentage of PICS in these very ill, older patients with significant comorbidities? Are you seeing 70%-80% developing PICS in that scenario?

Qadir: I am seeing numbers like that. The good thing is that things can improve with time. The way somebody looks at the time of hospital discharge is not necessarily going to be what they look like 3 months from now or a year from now. Some of these deficits can be long-lasting and really change patients' quality of life, how they view themselves, the type of caregiving they need.

There are so many reasons why we need to be more aware of PICS as providers. There are many patients who say that their clinicians don't know what PICS is, won't believe their symptoms, tell them it's in their head, or that they should just be lucky to be alive after what they went through. We need to be able to help these patients navigate a new reality in some cases and minimize the adverse effects of what happened. Again, if we're not aware of these things to begin with, we're not going to be able to do that.

Current Therapeutic Treatments for PICS

Glatter: The issue of psychiatric morbidity is really concerning to me. Some of the data about PTSD, anxiety, and depression in survivors from the ICU are just daunting in terms of the numbers. Close to 70% of patients have anxiety and close to 40% have some form of PTSD.

Are you using anything prophylactic to address this? For example, ketamine has been used to treat PTSD. It's very effective in terms of increasing connections between mood centers by increasing the density of synapses and dendrites. I'm curious if you've employed low-dose ketamine in some of your patients with PICS.

Qadir: That's a great question. Again, this is an area where we need more research in terms of preventing these things from occurring. Of the sedative medications that are used in the ICU, I do use ketamine from time to time, but I use it as a sedative agent or as an induction agent for intubation, for awake procedures in which you need some conscious sedation. As a sedative agent in the ICU, it's the one that has the least amount of data about it. I think it would be somethinginteresting to study.

It is a deliriogenic, which gives me some pause about its use in the ICU because I would imagine, intuitively at least, that it might increase the incidence of delirium, which then in turn can increase cognitive and psychological sequelae. I do think it very much holds promise for after the ICU. I think it would be challenging to study in the ICU, but I think it would be important to do so. We need more research in this area.

Glatter: In terms of sedatives like Precedex (dexmedetomidine), things like that, do you see any adverse effects from that? Compared to propofol use, we know certainly that can be deleterious for long-term use. Are you tending to use more sedative-type agents like Precedex?

Qadir: Precedex does seem to be associated with less delirium than some of these other agents. That's a bit controversial because if you are to use other sedative agents, like propofol, and maintain a patient relatively awake and comfortable, meaning not overdoing it, there may not be a difference between Precedex and propofol in terms of delirium. With Precedex, as anyone who uses it knows, you're not able to achieve deep sedation. Yes, we've used it. I feel like our use of it has definitely risen over the years.

Glatter: In terms of ventilation, are you trying to use more BiPAP and high-flow nasal cannula when applicable as opposed to maybe 5 years ago? Do you feel like the trend is now toward noninvasive ventilation in terms of that arena, when you can start weaning early, for example?

Qadir: Most of us are using high flow more often than before. I think when it comes to noninvasive and acute respiratory failure, there are many challenges, many caveats to be aware of, and a large amount of controversy in terms of who to trial on that.

Outcomes of patients with more severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) who get BiPAP tend to actually be worse. How can we use it effectively in patients with mild ARDS or in other situations? Aside from the evidence-based established ones like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations and heart failure, how to best use BiPAP and noninvasive ventilation in general in the setting of acute respiratory failure and ARDS, I think, is very much an area of controversy.

There is the risk for associated barotrauma that in volutrauma I think we underappreciate and which I unfortunately saw often over the course of the COVID pandemic. As with many things, the devil is in the details. There probably is a way to use these modalities safely and effectively, but we have to sort out exactly which patient population would benefit most. What are the things that we need to watch for? How long is a reasonable amount to keep somebody on these modalities? Those are all questions, specific to BiPAP and noninvasive ventilation, where we still need more data.

More on PICS Clinic Design and Role

Glatter: The population that you're treating in your PICS clinics are often patients who've been mechanically ventilated, if you look at the data across the board. I'd imagine, obviously, other subpopulations and cohorts exist, but that speaks volumes to who needs follow-up.

With that in mind, can you tell us a little bit about your PICS clinic, how it's designed, and the kinds of specialists who may help you out there, or are you doing this all with intensivists?

Qadir: Our clinic is multidisciplinary in nature, so we have a physician who is pulmonary/critical care, a respiratory therapist, a physical therapist, an occupational therapist, and a social worker, all of whom see the patient during the initial visit. Now, the ideal make-up of PICS clinics is not really known as of right now, and there's some variability in what kind of providers staff these clinics nationally. That's our set-up.

In terms of what we do, the things that I think are important are just to have a structured approach to diagnosis. For example, in order to screen for cognitive impairment, we typically conduct structured assessments like the Montreal Cognitive Assessment. Some other colleagues might use Mini-Mental Status testing or other structured tests. Without using these types of tests, you might miss issues just from taking a history and doing a basic physical.

We have similarly structured assessments for physical strength and psychological health. Those aspects are really important. Once we've identified the specific symptoms that the patient is having — which again, these scales, tests, and structured evaluations really help with — we can hone in and tailor our therapy to what those specific symptoms are for that individual patient.

The first steps are always going to be to address any potentially reversible causes. This can include things like medication side effects, which I see quite often, or newly diagnosed but yet unmanaged chronic conditions. Then supportive-care modalities like physical therapy, cognitive retraining, or pulmonary rehab can play important roles for many patients, depending on their symptoms.

I would say the majority of patients really benefit from ongoing physical therapy, and then things like cognitive retraining and pulmonary rehab, which tends to be a more focused subset of patients. Surprisingly, not everybody has ongoing pulmonary symptoms after recovering from ARDS. It's the weakness and the debility that impact the majority of people.

Glatter: Some of the data about PICS clinics are unclear as to whether it actually does lead to reduced mortality and improved outcomes. There's no standard fashion to design a PICS clinic. As you mentioned, it's tailored to the patient's needs. It might be hard to collect data and to standardize in terms of research.

Qadir: Absolutely. That's been a tough thing to research. As of right now, we don't know that PICS clinics improve mortality. Every PICS clinic at every institution is set up slightly differently, or maybe very differently, so we're not testing a uniform intervention. It's really hard to look for mortality changes in outpatient populations as well. There may be other outcomes that may be more appropriate, like readmissions, where I think PICS clinics show some promise in quality-of-life indices.

Glatter: In terms of loss to follow-up, are you finding that in patients who begin treatment in the PICS clinic? What kind of follow-through is there, based on your experience?

Qadir: Follow-up is challenging because most people don't go home after they're discharged from the hospital. They will go to a rehab center, subacute rehab, or an LTAC [long-term acute care facility] for some period before they're able to return home. While we aim to see people within a month after their discharge, that's not always possible because they may still be at another institution. There is some loss to follow-up that can occur there, and having a navigator to essentially keep in touch with the patients or their caregiver when that's the case can be very helpful.

In terms of longer-term follow-up, our goal is not to replace these patients' primary care doctors. It's essentially to help facilitate a smooth transition back to primary care and to any subspecialty care that the patient may need. For some patients, we'll see them once and they're doing well. We essentially will clean up their medication lists, ensure that they have the resources that they need (eg, if they need ongoing physical therapy and referrals to any subspecialty care), and communicate closely with their primary care doctor or establish them with a primary care doctor. Then we don't see that patient again because they're doing well and they have the resources that they need to continue improving.

With other patients, it really depends. Patients with ongoing cognitive issues or ongoing respiratory symptoms we may see multiple times before we transition them into primary care or regular subspecialty care. It really is tailored to the individual as to the number of times we see them. The first visit is very comprehensive, with the patient meeting with all of the various clinicians in the clinic that I mentioned. The subsequent visits are more tailored to the patient's needs.

Financial Resources and Allocated Funding: More Is Needed

Glatter: Speaking of resources, financially, patients and families can be devastated from these stays, due to loss of job, insurance, or the ability to come to the clinic if they don't have the ability to pay. What's in place in order to help these patients when they're struggling financially?

Qadir: That's a huge challenge. It's so expensive to be sick in the United States, especially, and there's a serious amount of financial toxicity involved here. People don't go back to work right away, and some might not go back to work at all. In turn, family often end up becoming caregivers, and with that sometimes they have to cut back on their own work and thus income.

Unsurprisingly, people who are less financially stable before their hospitalization are going to experience the impact of financial loss much more profoundly, which can impact both their mental health in an immediate way, from the associated stress, and also long-term health because they may have decreased access to a rehab or other resources, and the quality of those resources may be less.

We need more resources. As a physician, unfortunately I often feel a little bit helpless. We have video visits available for people who can't come in. That also becomes a barrier, like not even being able to travel. We have a social worker who connects these patients to various services that we have available in California, but it's hard. You can't replace somebody's lost income or their family members' lost income. If somebody has housing instability, my ability to do anything about that is quite limited. It's really hard to watch. I just feel limited in my ability to help, and so I feel like this is where we need social welfare programs to help.

Glatter: Making funding available for these clinics is so crucial. At the state level and federal level, that's something that MedPAC should look into and make it a concern, in my view.

Qadir: They're not RVU [relative value unit] generators, unfortunately. You can't just turn through a list of 20 patients in a day. You have to think about how this is a benefit to patients, and also potentially a benefit to health systems by possibly reducing readmissions. Then think about the fact that many patients will need referral and to the outpatient system — to primary care or other subspecialty providers. I think there are potential benefits from a system standpoint, but it's not going to be in terms of RVUs.

Glatter: Exactly. This makes me think of when patients bounce back to the ED, and the phenomenon of hospital-at-home. Can this PICS clinic extend to that similar concept of a hospital-at-home environment where they can receive services that they would normally receive in PICS clinic, either virtually or in person?

Qadir: Maybe in some ways. This is a very vulnerable patient population. Some of these bounce-backs are going to be unavoidable. PICS clinics can certainly reduce them by preventing some of the issues that occur after critical illness or catching them before they spiral out of control.

In terms of hospital-at-home, that's going to depend on the type of resources the individual has access to. That part's challenging. Being able to catch things before they turn into a bigger problem, that's a role that PICS clinics can play in terms of reducing readmissions.

As an example, I've had patients who came in to see us and still had indwelling devices like tunneled dialysis catheters that they no longer needed or didn't know how to care for, and that's just a bloodstream infection waiting to happen. If we're able to address things like that in clinic, that will keep them from seeing you in the ED. Another example is getting people with new or previously undiagnosed illnesses, like heart failure or diabetes, on appropriate medications before they end up decompensating and coming to visit you. Those are things where PICS clinics can play a huge role.

An ICU hospitalization costs a large amount of money. The healthcare system has essentially invested money into getting these people better. If you abandon them when they go home, what use was all of that? It's not just morally the wrong thing to do but also something that doesn't make sense financially.

Final Takeaways

Glatter: I agree. The moral injury, certainly, is so prevalent. Yes, you survive, but you may not recover. That's really the other side of things that we need to look at so carefully.

Do you have a few pearls for the audience that you could share?

Qadir: There are a couple of big things for ICU clinicians to think about. One, remember that everything we do in the ICU, even the things we don't always think very hard about, can have a lasting, lifelong impact on a patient. Second, and I would say is the most important takeaway, is that our work is not done after the patient has left the hospital, and surviving critical illness is not the same as recovery. We have to remember that our work is not done after the patient has left the hospital.

Glatter: Thank you so much, Dr Qadir. This has been so important. I appreciate your time.

Qadir: Thank you so much for having me. It was a pleasure talking to you about this.

Robert D. Glatter, MD, is an assistant professor of emergency medicine at Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell in Hempstead, New York. He is a medical advisor for Medscape and hosts the Hot Topics in EM series.

Nida Qadir, MD, is an associate professor of medicine and associate director of the Medical Intensive Care Unit at Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center in Los Angeles, California. She is also the co-director of UCLA's Post-ICU Recovery Clinic. Her research focuses on acute respiratory distress syndrome, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, and PICS. She serves on the critical care editorial board for CHEST, and has served as faculty for numerous regional and international critical care simulation courses. Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, she has co-directed UCLA's Disaster and Pandemic Response Team and served on the World Health Organization's guideline development group for therapeutics and COVID-19.